Our group has a long standing interest in superconducting proximity effect devices, or devices in which superconductors (S) are placed in contact with other materials such as normal metals (N), ferromagnets (F) or van der Waals crystals. The devices are in the micron to sub-micron size regime, and involve sophisticated multilevel electron-beam lithography to fabricate them. The primary interest is in investigating quantum coherent effects. In the past, we have studied such coherent effects in the electrical and thermal transport of proximity effect devices. Current interests are focused on searching for signatures of topological behavior in multiterminal SNS junctions and noise correlations arising from a process called cross Andreev reflection (CAR).

Multiterminal SNS Junctions

An electron in a normal metal N that is incident on a superconductor S cannot propagate into the superconductor if its energy E is less than the superconducting gap Δ of the superconductor. Instead, it is reflected as a hole with an energy -E with the concomitant generation of a Cooper pair in the superconductor, in a process called Andreev reflection. If another superconductor is attached to the normal metal N, the retroreflected electron in turn can be reflected as an electron, resulting in an Andreev bound state whose energy is a function of the macroscopic phase difference φ between the superconductors. This energy dispersion is similar to the energy dispersion of an electron with its momentum in a crystal. A SNS junction with two superconductors has one distinct phase difference, and therefore corresponds to the band structure of electrons in a 1D crystal. For a normal metal connected to n superconductors, there are n-1 distinct superconducting phase differences, and this n terminal SNS junction therefore corresponds to a n-1 dimensional crystal. There have been predictions that the resulting effective band structure can be topological in nature, even exhibiting features like quantized conductance between superconducting contacts.

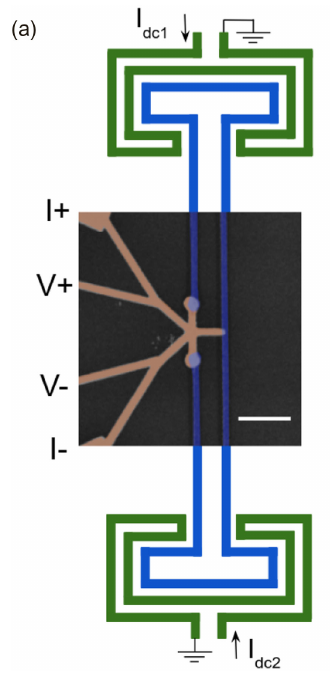

Our goal was to see if we could observe signatures of topological behavior in the conductance of such devices. Figure 1 shows a false color SEM image of a 3-terminal SNS junction. The two independent phase differences in such a device are tuned by using flux loops and on-chip field coils (shown schematically in the figure). By varying the current through the field coils , one can independently tune the flux through each flux loop, and hence the phase difference between the respective superconducting contacts.

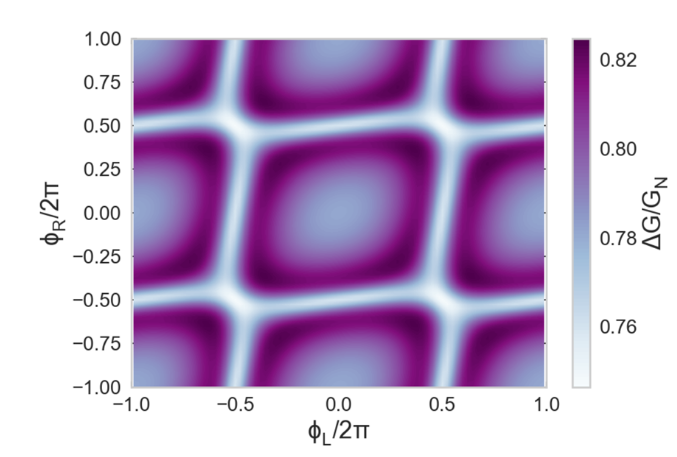

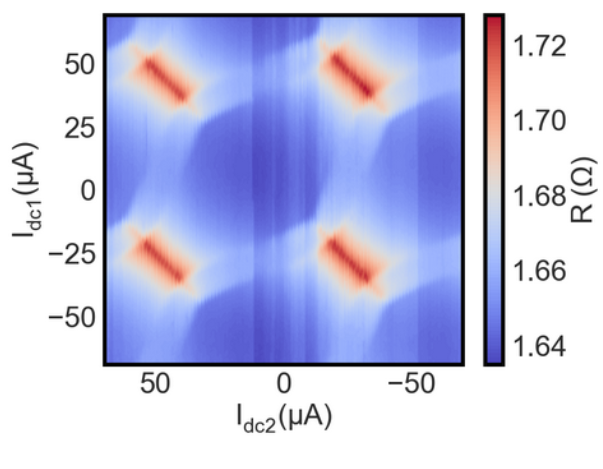

Figure 2 shows the calculated conductance of a 3-terminal SNS junction as a function of the two independent phase differences. The calculations are performed using the quasiclassical theory of superconductivity. The structure is periodic, similar to the momentum space dispersion of electrons in a crystal, reflecting the underlying periodicity of the density of states in the normal metal. Figure 3 shows the experimentally measured resistance as a function of the currents applied to the two on-chip field coils. The structure is remarkably similar to that of Figure 2, although the experiment shows more detailed fine structure than predicted by the calculations. No distinct signatures of topological behavior have been found, however. We are continuing measurements on such multiterminal Josephson junctions.

Using Cross-Correlation Noise Measurements to Probe Quantum Coherence

For a three-terminal device with two normal-metal wires separated by a superconducting wire, it is interesting to know whether the electrons in the two normal-metal wires are in a quantum entangled state induced by the adjacent superconducting wire if the separation between them in the superconductor is small enough.

One possible microscopic process that can induce the entangled state is called Crossed Andreev Reflection (CAR), discussed above. The physical picture of CAR process can be thought of as follows: near the two normal-metal/superconducting interfaces, one electron from each of the two normal-metal leads is converted simultaneously to (or is emitted from) a Cooper pair in the superconducting wire. Since the electrons disappear from the normal-metal wires at the same time, they are positively correlated and the currents flowing through the NS interfaces should also be positively correlated. One the other hand, it is also possible that the electron can tunnel from one normal-metal wire to the other without being converted to Cooper pair, a process called Elastic Cotunneling (EC). In this case, due to the Pauli principle, electrons will tunnel one by one and this leads to negative correlation.

A simple transport measurement can not identify whether the correlation is positive or negative since it only gives the average value of the current. In contrast, a measurement of the current-current correlation is capable of separating the contribution from CAR and EC, thus determining whether or not there is an entangled state. The magnitude of the correlation is determined by the ratio of the separation distance between normal-metal wires over the superconducting coherence length.

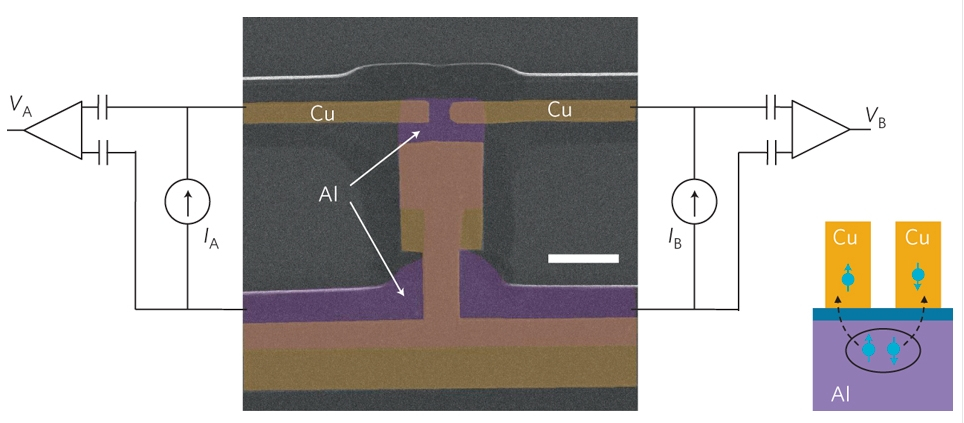

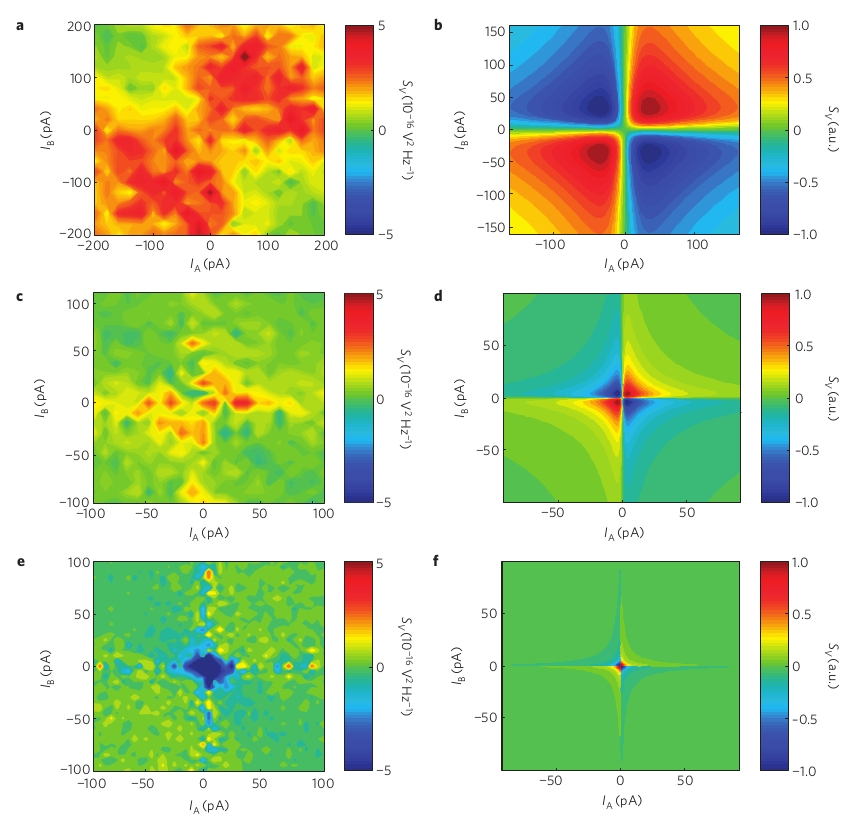

In order to differentiate between EC and CAR using noise measurements, we use a sample like that shown in Figure 4. This has two normal leads connected to a superconductor through tunneling contacts. Theory predicts that if the current through each junction is in the same direction, then CAR will be favored, while if they are in opposite directions, EC will favored. The signature of CAR is a positive correlation in the noise across the two junctions, while the signature of EC is a negative correlation. Figure 5 shows the measured cross-correlation noise across the junction as a function of the bias currents IA and IB. While a positive cross-correlation is indeed seen when the currents are in the same direction (a signature of CAR), essentially no correlation is seen when the currents are in opposite direction. At lower temperatures, a large negative cross-correlation is observed near zero bias, which we believe might be associated with the dynamical Coulomb blockade.

These measurements were carried out using low-frequency measurement techniques. We are currently trying to make the same measurements in the microwave frequency regime, which will increase our bandwidth, and hence improve our signal-to-noise ratio. We are also trying to study analogs of the Fermionic Hanbury Brown and Twiss experiment with devices of this type.