As part of the SQMS Center, we have been studying the properties of superconducting materials and devices in order to determine the factors that limit the performance of superconducting qubits. Earlier work focused on measuring the quality of Nb films grown by different techniques using phase boundary (Tc vs H) measurements. Current work focuses on studying quasiparticle dynamics in superconductors and noise in Josephson junctions and transmons.

Current voltage (IV) characteristics and noise in Josephson junctions and transmons

The heart of superconducting qubits is the Josephson junction (JJ), a superconductor-insulator-superconductor (SIS) junction that acts as a nonlinear inductor in parallel with a capacitor. A critical parameter that determines the quantized energy levels of the qubit is the Josephson energy EJ, which in turn is determined by the critical current Ic of the junction. For most of the superconducting qubits that are fabricated, Ic is determined using the Ambegaokar-Baratoff formula, which relates Ic to the low temperature normal state resistance Rn of the JJ and the energy gap Δ of the superconductor. More often than not, EJ is estimated from room temperature measurements of Rn and the textbook value of Δ. Our initial goal was to obtain accurate measurements of these quantities by measuring the low temperature current voltage (IV) characteristics of these junctions. The so-called quasiparticle branch of the IV characteristic should directly give a measure of both Rn and Δ. To this end, we measured the low temperature IV characteristics of more than 20 different JJs fabricated in house as well as by our collaborators in the SQMS Center.

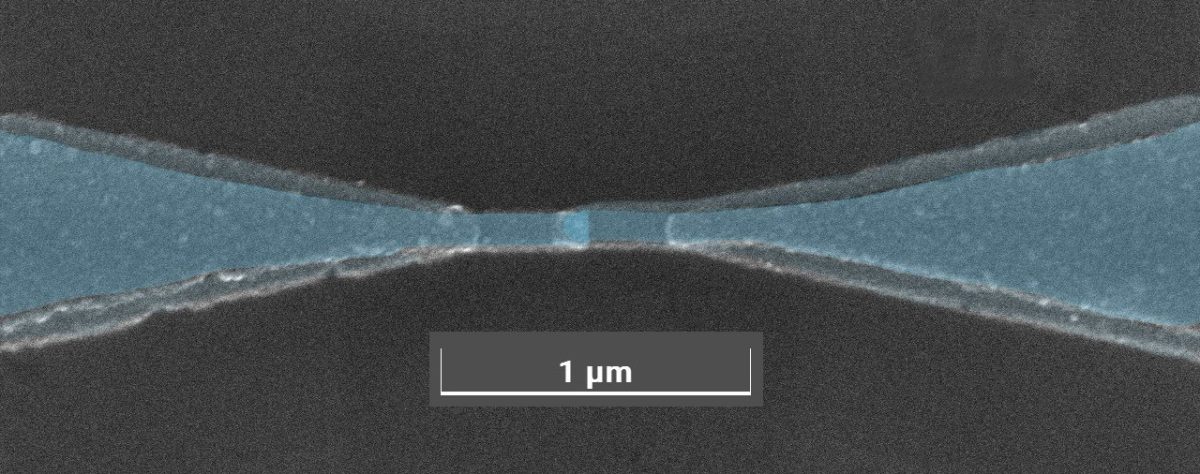

Figure 1 shows a false color SEM image of a small area Al/AlOx/Al Josephson junction fabricated by electron beam lithography at Northwestern using the Dolan bridge (angle-evaporation) technique. In addition to junctions fabricated in-house, we have also measured junctions fabricated by our collaborators in the SQMS collaboration, including Rigetti, Fermilab and NIST. These include isolated JJs as well as JJs shunted by large capacitors, forming a conventional transmon qubit.

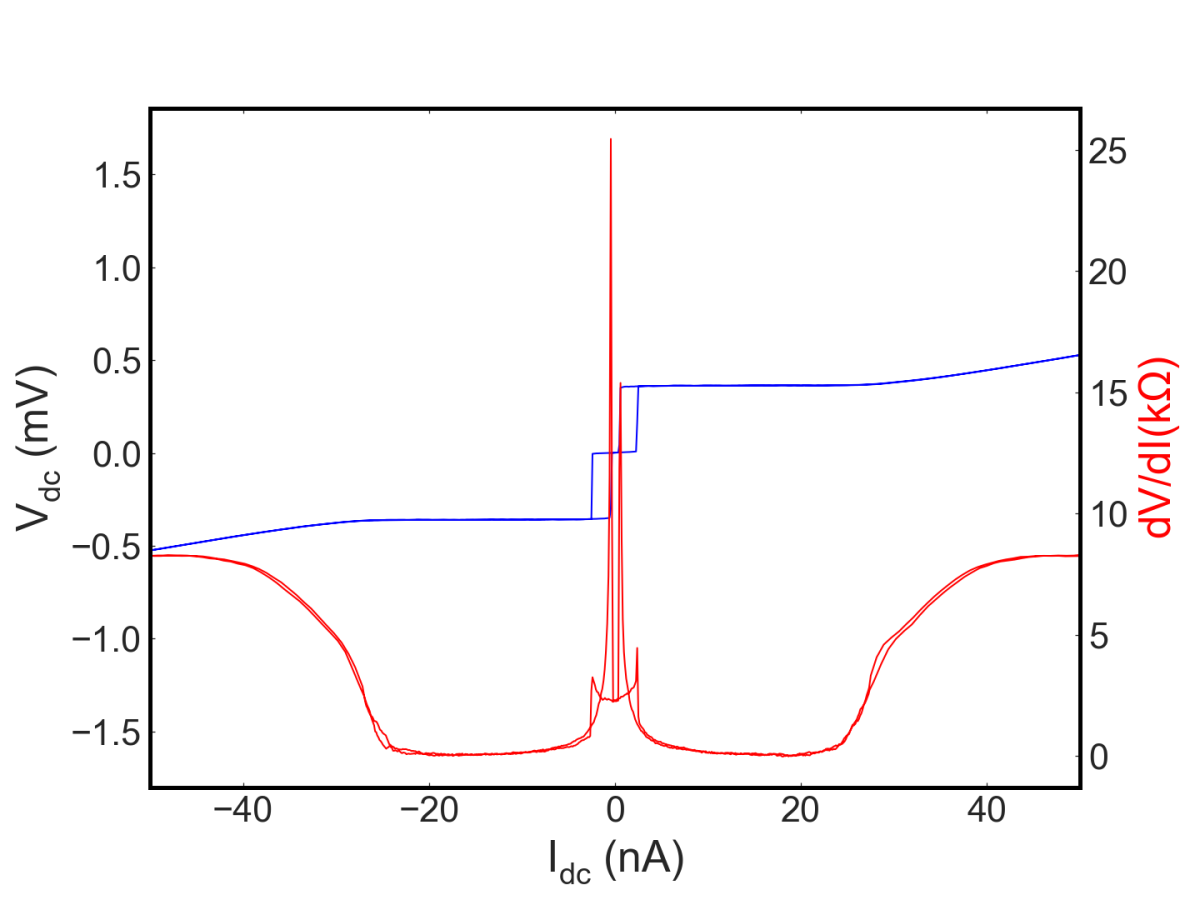

Figure 2 shows the IV characteristic of an isolated JJ measured at 24.5 mK. For these measurements, we current bias the junction with a dc current as well as a small, low-frequency ac current to enable simultaneous measurements of the voltage across the junction as well as its differential resistance. From the conventional picture of electrical transport through a JJ, one should be able to apply a dc current through the junction up to a value corresponding to Ic with no voltage drop across the junction (and hence no differential resistance). For I>Ic, there is a sharp switch to the quasiparticle branch of the IV curve, and the voltage at which this switch occurs corresponds to 2Δ/e, giving a direct measure of the gap of the superconductor. In addition, the slope of the IV curve at high (current or voltage) bias gives Rn. As noted earlier, with these two parameters, one should be able to estimate Ic and hence EJ using the Ambegaokar-Baratoff formula.

Estimating Ic from the Ambegaokar-Baratoff formula using these parameters measured directly from the IV of Figure 2 gives an estimate of ~30 nA. However, the current at which the JJ switches to the quasiparticle branch is ~2.5 nA, more than an order of magnitude smaller than the theoretical estimate. In addition, a closer look at the voltage across the junction below even this reduced critical current shows that it is not zero as would be expected for a conventional JJ, but finite. This can be seen more clearly in the differential resistance, which shows a finite differential resistance of ~2-3 kΩ when Idc~0. We have measured more than 20 small area junctions fabricated in a number of different institutions, and all have shown similar low-temperature behavior.

While such behavior may seem surprising at first, it has been observed by a number of different groups in the 80s and 90s, and is attributed to the small capacitance of the junctions. In the well-known resistively and capacitively shunted junction (RCSJ) model, the dynamics of the JJ can be mapped on to the motion of a fictitious “phase” particle in a tilted washboard potential with a spatial parameter corresponding to the phase difference φ across the junction, with the “mass” of this phase particle being proportional to the capacitance C of the JJ. A particle with smaller mass is more susceptible to being buffeted by noise, and hence its position will shift: as the “position” in this model corresponds to φ, and as motion in φ will result in a finite voltage across the JJ due to the ac Josephson effect, the fictitious particle might diffuse to neighboring minima of the washboard potential even at 0 dc applied bias, leading to a finite voltage and hence a finite resistance. It is also more likely to prematurely transition to the “freely running” state, where it continues to travel down the washboard potential, corresponding to a premature switch to the quasiparticle branch of the IV characteristic at currents much less than the nominal Ic of the junction.

Thus, our observations are not surprising, given the small intrinsic capacitance of the isolated JJs. What is surprising, however, is that we observe the same effects in so-called transmon qubits, i.e., JJs that are shunted by large capacitors to minimize susceptibility to noise. Our results suggest that at least some level, it is intrinsic capacitance of the JJs that determines their susceptibility to noise.

Current research is focused on directly measuring the noise of these JJs using cross-correlation noise techniques.

Quasiparticle dynamics in superconductors

Quasiparticles in the superconducting regions of a superconducting qubit are detrimental to their coherence times as they can modify the energy spectrum of the qubit, or couple to the phase degree of freedom of the qubit. Given the size of the energy gap in the typical superconductor used to make the JJs in qubits (usually Al), the expected population of quasiparticles is expected to be exponentially small at the usual operating temperatures of the qubits (10 mK). Experimentally, however, the quasiparticle population is found to be many orders of magnitude larger than this. The reason for this is not clear: it has been variously suggested that this might be due to two-level systems (TLSs) or to cosmic rays. While many groups are attempting to reduce these sources of quasiparticles, other efforts have focused on mitigating the effects of quasiparticles already in the device. A well researched technique is gap engineering, where the superconducting gap is spatially modulated using the proximity effect such that areas further from the critical junction have smaller superconducting gaps, so that quasiparticles that diffuse to these regions are unlikely to diffuse back to the larger gap area near the JJ itself.

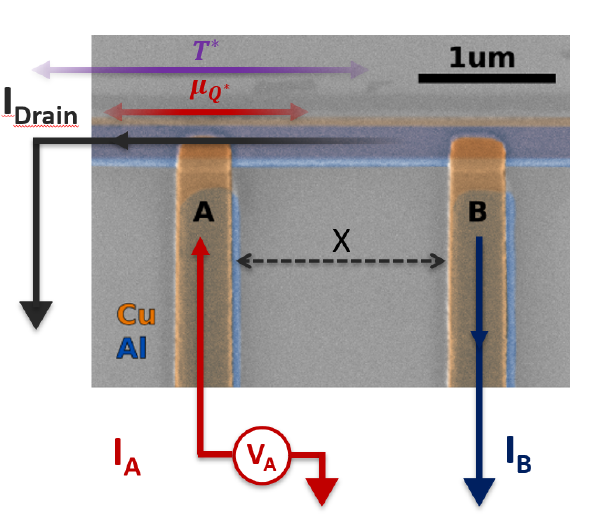

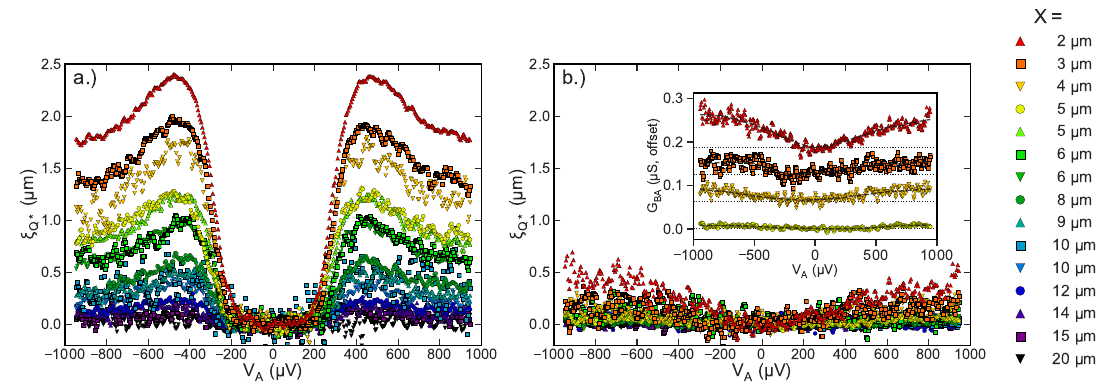

Our focus is on seeing whether one can reduce the deleterious effects of quasiparticles by enhancing their relaxation rate. To study the dynamics of quasiparticles, we used nonlocal measurements using normal metal/insulator/superconductor (NIS) junctions. Figure 3 shows a false color SEM image of one of the devices measured. It consists of a superconductor (Al: blue) with two evaporated normal metal contacts (Cu: gold color) with a thin AlOx tunnel barrier between the normal metal and the superconductor. Quasiparticle current can be injected using one of the normal contacts, and nonequilibrium quasiparticles can be detected by measuring the current or the voltage at the second NIS junction. The voltage across each NIS junction can be varied independently, so one can perform such spectroscopic measurements as a function of injector and/or detector bias. By varying the distance between the injector and detector junctions, we can measure the decay length of the diffusing quasiparticles. Two different types of devices were measured: one with a thin (~3 nm) normal metal under the superconductor (Al) to create a proximity bilayer (as can be seen in Fig. 3) and a control sample with just the superconductor (Al).

Figure 4 shows the nonlocal conductance as a function of injector bias voltage VA for various separations between the injector and detector junctions. The voltage bias of the detector junction is kept at zero, and the data are normalized to take into account differences in injector and detector junction conductances. The left panel (a) corresponds to injection into a pure superconductor (Al), while right panel (b) corresponds to injection into a superconductor (Al) with a thin (~3 nm) normal metal layer (Cu) underneath; both being plotted on the same scale to emphasize their differences. In (a), one can clearly see the decay of the nonlocal signal with distance between the injector-detector junctions, corresponding to a decay of the injected quasiparticles with a characteristic decay length of a few microns. The normalized conductance in (b) is clearly much smaller than in (a), showing that the presence of the normal metal results in a drastic decrease in the decay length of the quasiparticles, or equivalently, a drastic increase in their relaxation rate.

We believe that the decrease in the relaxation length is not due to quasiparticle trapping, but due to increased quasiparticle relaxation due to the presence of the thin disordered Cu film. Theoretically, the quasiparticle relaxation rate is expected to be proportional to the electron-electron scattering rate in the corresponding normal state of the superconductor. This rate depends on the degree of disorder in the film, being enhanced when the film is more disordered. The introduction of the thin, highly disordered Cu film therefore increases the relaxation rate of quasiparticles in the bilayer. Note that depositing a thin Cu layer beneath the Al superconductor does not significantly modify the properties of the superconducting film, so this is a technique that can readily be adapted to making Josephson junction qubits.

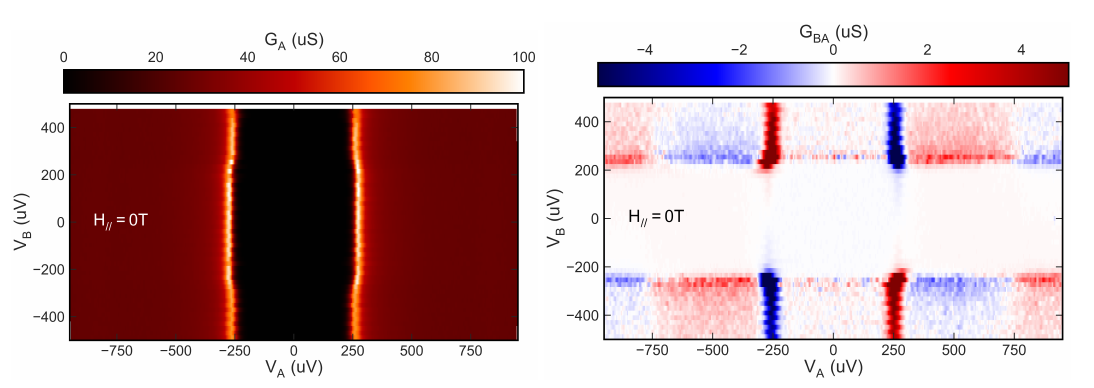

While the data shown in Fig. 4 are for zero voltage bias on the detector, one can also apply a finite voltage VB on the detector while measuring the local and nonlocal conductance. Figure 5 shows the local (left panel) and nonlocal (right panel) conductance as a function of the injector (VA) and detector (VB) biases. The local conductance shows a suppression of the gap parameter when the detector bias exceeds the gap. This is expected, as a finite population of quasiparticles is known to suppress the gap. The nonlocal conductance shows much more structure, including antisymmetric dependence on both VA and VB. We are currently investigating the origin of these asymmetries.